(I think you'll be glad you stuck with me through this part of Certified. I really do learn from my adventures. Also, I do have some photographs this time, but I was having trouble with my camera, so they aren't the best. I've also put in more links than usual, but I hope you find them useful.)

Chapter Ten

During the month between residencies, I finished up Jewelweed Station, a novel I had been working on since late winter. It felt great doing something I loved, being comfortable with it, having fun with the story. I fell in love with writing again--or else I let the disappointment of my publishing experiences evaporate and I could see that I still loved writing.

I also worked on my master plan for the permaculture class and my final project for integrative environmental science.

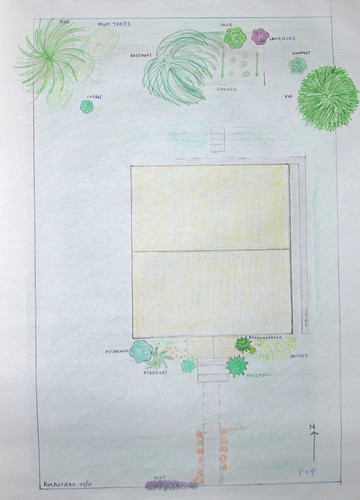

First I mapped my house and property the way it is now. (We rent.) For the master plan--or the "poof!" plan as the instructor calls it--I needed to permaculture our house and property (at least on paper). Incorporating much of what I'd learned all term, I let my imagination soar.

First I put in a rain catchment system to harvest my rainwater. I calculated that if I caught all the water from my roof, I'd get 68,000 gallons in a year! Wow. (Even someone in the desert can harvest quite a lot of water from their roof.) Even without filtering or cleaning the rainwater from the roof, I could use the rainwater to water much of my garden, particularly the perennials (where I don't eat the leaves), and to flush the toilets (about 10,000 times).

I also put a couple of solar panels on the front of the house, plus a solar water heater. In most houses, water heaters use a lot of energy, so a solar water heater would save us lots of money (besides helping to reduce overall energy use).

Mostly my poof! plan had lots and lots of food. What I've learned about permaculture (and about ecological gardens) is that we have the potential for amazing abundance in our own backyards, no matter how tiny or unproductive they seem to be. I live on a small lot, yet I was able to design for apple, walnut, and cherry trees. (We've already got several prune plum trees.) I also designed for mulberry and blueberry bushes, plus espaliers of apples, pears, and berries. I planted maples trees for shade, and lots and lots of wildflowers because I love them, and because they're good for the birds and butterflies. I put in a huge vegetable garden, and I made room to "grow" worms.

(In permaculture, we design for diversity, and everything has multiple uses. For instance, daikon radishes break up the soil, plus they're edible. An apple tree provides shade, flowers for the bees and butterflies, and fruit for people and animals. Other plants fix nitrogen and provide food. Other plants are beautiful for us to look at, plus they provide habitat for the birds and the bees and are drought resistant. And on and on.)

My before-permaculture drawing showed a sweet-looking, but rather barren landscape.

The after-drawing, the permaculture poof! plan, was so filled with color and life--so much abundance.

The most important thing the permaculture class taught me just that: the possibility for abundance is everywhere. We just need to do some work and then within eighteen months (or less or more), we're not thinking about what we don't have, but about what we're going to do with all the abundance.

For my integrative environmental science project, I had planned on designing an ecological garden for the community library. For the final presentation, I decided that each of my fellow students would play the part of a community member while I talked about the ecological library. I wrote little (compassionate) biographies of people in town who help out with the library. (I changed their names.)

Most of the students live in an urban area and don't do any work in rural areas. I wanted to give them an opportunity to walk in someone else's shoes and see what their reactions might be to this proposed changed.

I finished both projects well before I was due to leave for Seattle. Yes!

Our car was acting up, so I decided to rent a car to go to Seattle. I wouldn't have to worry about breaking down and there would a CD player in the rental, so I could listen to a book on CD. I was hoping that would help make the drive up to Seattle more sustainable.

And I was right. The drive to Seattle was eventless. No rude drivers. No traffic jams. I listened to the second have of Manhunt, the true life story of the hunt of John Wilkes Booth after he murdered President Lincoln. (I'd listened to the first half while driving from Phoenix to Santa Barbara in February.)

I was almost in Seattle when the car went over a patch of bumpy pavement, and I had a bout of vertigo. I was immediately nauseated and terrified. I realized then that the car had been "wobbly" the whole ride and it had made me a little car sick.

I got to my "home" in Seattle, the little room in the house owned by a religious community. Unfortunately the key they'd left for me didn't work. I could get into my room but I couldn't lock it. It took me a while to convince the young woman on the other end of the phone that being able to lock my room was important for me. Eventually she seemed to understand; she arranged to get me a key, and all was well in my little world.

I was still feeling sick and dizzy, so I drove to campus (University of Washington), parked my car, and walked to the Medicinal Herb Garden. Last time I'd been there, I had been waiting for the class. (If you remember, I went to the wrong place and I waited for about thirty minutes for classmates that never came.) This time I walked slowly around the garden, looking at the flowers and plants, trying to ground myself and feel better.

After a few minutes I walked over to a huge old cedar tree. I rested my cheek against it, then sat on a bench beneath it, meditating. I felt as though I was sitting near Yggdrasil, the World Tree. I breathed in and out, in and out. I could hear the buses running outside the garden, saw students walking on the paths around the gardens, and I breathed and tried to relax.

After a while I got up and walked toward a small orange flower. It turned out to be jewelweed, a plant I'd never seen but had starred in the novel I'd just finished.

In it, Callie noticed one lone jewelweed growing by her mother's grave. "Jewelweed. Usually it grew closer to the water and was surrounded by other jewelweed. It was one of her mother's favorite flowers. Her mother said people often didn't see jewelweed or ignored it all together if they did see it even though it was a great healer. Get stung by nettle or touched by poison oak and the juice from jewelweed would sooth the inflammation away. Her mother believed wildflowers could fix anything."

It was nice to see this plant here and now. I started to walk away. I turned and everything in the background became blurry, as though I had moved too quickly for my vision to keep up. This had happened before, usually when I was tired, but just then I felt a little afraid and vulnerable. Was something happening to my vision? I turned quickly again to try and make it happen again.

It didn't.

I told myself to calm down. Maybe it wasn't anything physical. Maybe something energetic was happening in the garden. I walked to the other end of the bed, to see what was growing with the jewelweed.

I had to laugh: It was black cohosh.

I didn't know a lot about black cohost, but I recalled it was considered to be a powerful "women's herb." I decided to sit next to it and meditated on it. Immediately I "saw" a powerful witch-like Kali-like figure. She was dark purple and full of motion. She had lots of advice for me. Mostly I knew I could call on her to fill me up with courage. (This was interesting to me. In Jewelweed Station, my main character, Callie Carter, pretends she is docile and compliant, and when she had difficulty with this, she fills herself up with Jewelweed. This gives her the courage to hide and protect herself, to gather information and power, until the time is right to reveal herself.)

I thanked the plants and trees. Then I drove to Whole Foods and got some food. I went back to my place, watched two Netflix DVDs of Entourage, then fell to sleep. I thought of black cohosh before I drifted to sleep.

I dreamed someone phoned me, and the person sounded just like my mother. I was so excited to hear her voice. But as I talked with this person, I realized it wasn't her, and that made me very sad. In another dream, I was talking to my boss about a dream I'd had about him. He had huge white teeth in the dream. He told me my dream was right. He did get a backache and he read Healing Back Pain and it went away.

Healing Back Pain is a book by John Sarno that saved my life. My friend Jenine recommended it to me when I was suffering from acute back pain. Dr. Sarno believes most back pain (and many other symptoms) are caused by oxygen deprivation that occurs when we suppress our emotions.

When Jenine first pointed out the book to me, I was pissed. I thought, how dare anyone suggest this agony I'm experiencing was all in my head? Except that wasn't what he was saying. I read the book in one sitting, came up with a kind of mantra/affirmation and said it every time I woke up in pain that night, and in the morning the pain was gone.

It was a miracle. Truly. I've given that book to many people over the years. I guess in my dream I had recommended the book to my boss.

I also dreamed I saw a car go over an embankment and flip over. I ran to the car, but we couldn't get the injured woman out. She curled up into a fetal position. I put my hands just above her and gave her a healing to try to keep her alive until the EMTs arrived. It worked. I saved her life.

The next morning I drove to campus for my permaculture class. Seeing everyone again was like seeing a group of old friends. We did a check in at the beginning of class. He wanted to know what we had learned in the class--one or two points that really stuck out for us.

I said, "I've learned that somewhere along the line, I turned into a control freak. Not about other people, but about myself. I learned that I don't like doing things I'm not good at. I don't want to start things until I know everything. I learned that I can actually do things without knowing everything. I pulled out a whole patch of peas that were infested with aphids. Normally I would have gotten depressed--or at least angst-ridden--about my failures as a gardener. Instead, I figured this was just a learning process for me. Next year I'd do different and better. I've learned that everywhere around me is the potential for abundance. Everywhere around me are solutions. I love that. I've learned to let go."

Yep. I didn't plan to say any of that. It just came out, and it was all true. Perfection was not needed--was not even obtainable. I could make mistakes, and it was not the end of the world.

We watched a movie and talked; then we looked at all our master plans--our "poof" plans. We hung the before and after drawings next to one another. It was such fun to see the abundance, the liveliness, the wonderful imaginations of each person expressed in this particular way.

After lunch, we all met at someone's house in Seattle to look at their permaculture garden. Next we were supposed to meet somewhere in Shoreline. I had a map. People offered to take me with them; I should have let them. I ended up driving around for two hours, feeling sick and dizzy in that car, and I never found my class. I did finally find what I thought was the right address, but it looked like a crack house, and there were no cars out front, so I figured it was the wrong place.

It didn't feel like this was the end of the world. I was not angry at my teacher, my class, or myself. But I was feeling a little sick from the car.

I went back to my place and curled up in my bed. I called my friend and said I wasn't sure if I was up for going out. I'd invited her out to dinner, and now I was canceling. I felt like a whimpy jerk. I told her I'd call later.

I got some food from the refrigerator in the hallway. Then I put Pride and Prejudice in my computer, got under the covers, and vegged out. My dizziness and nausea settled down. I called my friend again and we decided to go out.

She picked me up when it was still light, so I suggested we drive to the Medicinal Herb Garden. We had both taken the Celtic Shamanism Two-Year, along with Faery Doctoring, so I knew she would appreciate the garden. We parked and walked along the curving tree-lined street. And then we were in the garden, walking from this garden bed to the next.

It felt like fall had set in: many of the herbs had no flowers, some of the formerly plump stalks had dried out and turned beige and golden. Of course, this wasn't any different from the evening before, but I noticed a bit more about the garden this night than I had yesterday. The piece-de-resistance was the ancient tree. My friend noticed that it seemed as though it was really two trees: one tree was enveloping another. Was it actually two trees?

It turned dark quickly, and we were soon driving around Lake Washington down a dark and narrow road. I was so exhausted that my anxiety was vanquished, and I only thought vaguely about the possibility of crashing into oncoming traffic. We passed the Japanese Gardens. Then we were out of the woods and on Madison. My friend parked the car, and we walked to Cafe Flora.

We had a great dinner and great conversation. I was still a little spacey and dizzy. This often happens to me when I'm one on one with someone. I don't know what it is. Some kind of unconscious stress or shyness emerges--or tries to emerge--but I tamp it down so hard that I don't feel any emotions: I just feel sick.

It ain't easy being green, and it ain't easy trying to figure me out.

I'm great with crowds, by the way. I've always kidded around that this means I'm great with shallow relationships and not so good with deep relationships. I actually do connect with groups of people much better than I do with individuals.

Anyway, we had a good time, and then I went home to sleep.

I had nightmares about people trying to kill me. I also dreamed Mario and I saw a jaguar in the woods. The jaguar was walking away, but he turned and saw us. Then he started coming our way. This was quite frightening as we tried to figure out how we'd get away from him.

I got up early, ate, packed, and put everything in my little nauseating rented car. I said good-bye to my little room in the basement; then I left.

It was great getting to school and seeing everyone in my integrative environmental science class. Many of them were in my permaculture class, too, and a few asked me what happened, where had I been yesterday afternoon.

I said, "I drove around nearly two hours trying to find the class. But I couldn't find you all. I guess my role in the forest garden is to get lost."

I laughed and shrugged. It was good to see that my perspective had changed over the last two months. I didn't take it personally that I couldn't find the class; I didn't take it personally that I had gotten lost. It wasn't a character flaw on my part or a rejection by the community on their part.

I just got lost.

Should have gone with someone else.

No big deal.

We started presenting our final projects. Three of us had individual projects. The rest of the class had worked in pairs or in triads. The teacher had posted the order of our presentations: I was last. I wondered if everyone would be exhausted by the time I presented, but I didn't worry about it. If they were tired, I'd change it. I was good at sussing the energy of a group and then flowing with it.

The first presentation was on climate change. Three of the students were working to help the city of Seattle go carbon-neutral. During their presentation they showed NPR's Robert Krulwich's five-part cartoon video called "Global Warming: It's All About Carbon." (It was so funny! I highly recommend it. Click on Episode 1 & watch in order; for some reason this link goes to Epi 5.)

That was the highlight, but the others were good too. One duo talked about the green belt in Seattle. Another talked about a transit station going up in their neighborhood. They were all different. All informative. Everyone was engaged and enthusiastic.

And I was last.

I had them push away the tables and put their chairs in a circle in the middle of the class. I asked them to leave all computers and cellphones behind. Someone asked why, and another student said, "Because she doesn't want us texting during her thing." She smiled. "I don't know what I'm going to do."

She was exactly right. I had noticed people texting and checking their email while others were presenting. I wanted to see what would happen if we were all in a group really together, elbow to elbow, breathing each other's air.

At first, some of the students looked quite uncomfortable. I explained that they were each going to take on the role of someone else, a real person from my community. I wanted them to act and ask questions from the viewpoint of that community person. I would tell them afterward what really happened at the real-life presentation that I had given a month or so earlier.

"You'll already know everything I'm going to say about a permaculture and ecological garden," I said, "but it was mostly new information for the community when I made the presentation. I also gave you information about these people's personal lives because it's important to realize that everyone working on a project has something else going on in their lives. We've all got people we love who are in trouble. Or we're struggling with our health or our jobs. Something."

I had written up the biography of each person and put it into an envelope and sealed it. On the outside I put the name, sex, and age of the person. Most of community members were well over sixty years old. I instructed the students not to open the envelope but just to take in the name, age, and sex.

"If you're working in communities and neighborhoods," I said, "you will often be working with people who are very different from you. I am often the youngest person in the room and that's been true for a long, long time. I think it's good to be aware of the differences and to not judge people just because they're older than you are or because they live in a rural community, or whatever. It doesn't mean they're stupid or uneducated. Some people live away from the city by choice."

I instructed them open the envelopes. I began my presentation. The energy of the group quickly shifted. People were soon asking me questions from the viewpoints of their "characters." It was quite invigorating! One person was concerned that things wouldn't be neat enough in the garden. Another person wanted it to look more wild. Someone else was worried about the cost.

I answered their questions. One person kept asking the same question again and again. I wasn't quite sure how to answer the question differently. But the person asking it was very perceptive: often in these kinds of situations people do ask the same question again and again, even after you think you have answered the question adequately.

It was a wild and crazy presentation. Very dynamic. I loved it. I felt like we were a real community. I was laughing when I ended it and thanked them all.

We remained in the circle to close. People thanked me for my presentation. We talked about our time together. And then it was time to go.

As usual, I was the first to leave. I got in my little rented car and drove out of Seattle. I thought about the summer.

I remembered how lost and alone I had felt when I first started this program. I had felt so out of place. I was older than almost everyone. I was one of only two people who lived in a rural area. I had felt like a country bumpkin around a bunch of young city people.

But none of that had been true. Or rather, none of that was real. I had been projecting my own fears onto this experience. Once I let go of those projections, once I relaxed a bit and recognized my part in my frustrations, once I gave myself a break, reality was made visible.

A reality was these were great classes where I learned a lot about my world and myself.

But something else happened during these ten plus weeks.

I faced some facts about my life--always a difficult thing to do. I had a family member who was struggling with drug addiction. She had gone into rehab for three months, and she now had the skills to help herself and to get help, but she wasn't doing it--at least she wasn't doing it enough to keep herself from relapsing. Every day for weeks, I had worried about getting a phone call that she was in a coma or a car accident. Every night I feared I would get a call from someone telling me that she was dead.

I tried to get her help from afar. I tried to talk with her and encourage her. But I was often speaking to her when she was high, and I didn't always know the difference. Later she wouldn't remember what I'd said or anything about our conversation. And she lied so fluently, so easily. Lying is the second language of addicts.

We hear again and again that addiction is a disease. I knew that. But I kept telling the rest of my family, "If it's a disease, then we have to do get her help. You don't tell someone who's having a heart attack, 'if you really want help, you call 911.'" How could it be a disease AND one still had to get help themselves?

I didn't get it for a long time. Then I realized that my family member's addiction was ruining my life. It was affecting my husband. It was affecting everyone in our family. Different family members had tried to help her. My father, only six months out of dangerous heart surgery, travelled out to stay with her. She remained straight while he was there, but as soon as he was gone, she relapsed. I thought seriously about going to live with her for a time, but then I had a flashback to last winter when I'd gone to Arizona. I had spent half my time trying to save her.

I couldn't save her. If I went down to live with her, I would be miserable and it would just delay the inevitable: when she would have to save herself.

I had started this program in Seattle because I felt hopeless and helpless about the oil gushing into the Gulf of Mexico. I had wanted to save the Gulf of Mexico. I have always wanted to save the world.

I have always wanted to save this particular family member. I felt like I had been trying to save her my entire life.

Once she told me she wanted someone to love her so much that they'd feel like they'd die if she died. She wanted someone to love her so much that they'd give everything up for her.

I told her no one would ever love her like that: no one except herself.

She had to save herself. She had to grow up and save herself.

My relative isn't alone in this desire. I've heard other people say similar things. They're waiting for someone else to save them. Some politician. Some leader. Some spiritual guru.

It ain't gonna happen.

We've got to grow up and save ourselves. It is a profound lack of maturity which causes us to put our heads in the sand.

We've got to act like adults and solve some problems.

My family member is comfortable in her addiction. I think many of us are comfortable in our addictions--we are comfortable with our comfort.

I know I am.

Or I was.

I now know I can't save my family member. I hope she can save herself. I hope she can love herself enough to put herself first, before her comfort. To save herself.

I was extremely uncomfortable during the course of these classes. I made so many mistakes. I made so many judgments. I was hard on my classmates and teachers. I was very hard on myself. But I kept doing the work. I kept going forward. And eventually, through all the smoke and mirrors I was tossing up, I saw the possibility for abundance. For abundance in the world and in my life.

It won't always be comfortable. It will definitely be messy. But I know we can plant it, grow it, build it, create it, let it happen.

Poof!

There it is.

I got home safe and sound.

Ain't it grand?

Read more here...